HOW I CAME TO LOVE SEAM-BLENDING

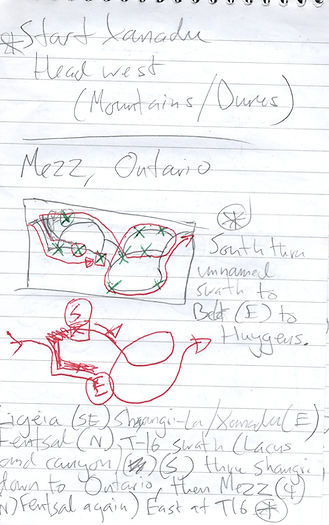

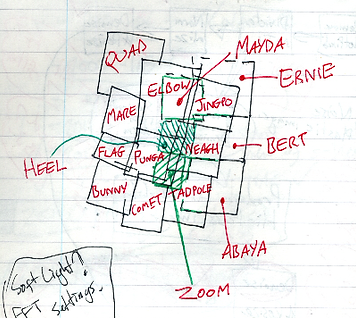

Figures 2: Radar ground track (rough sketch)

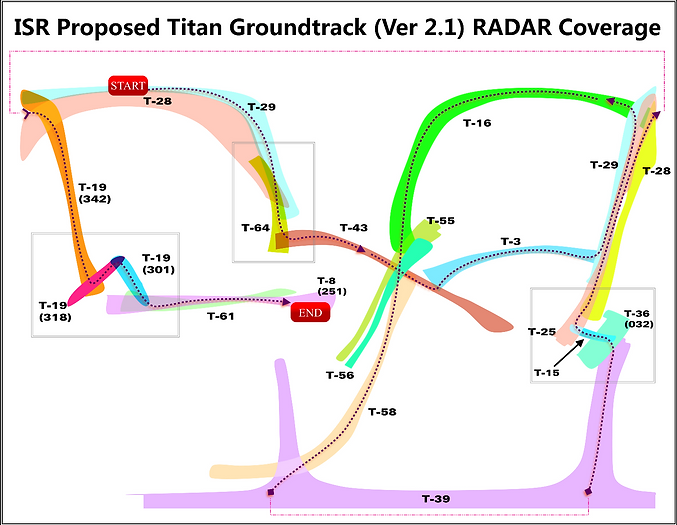

Figures 2: Radar ground track (final version)

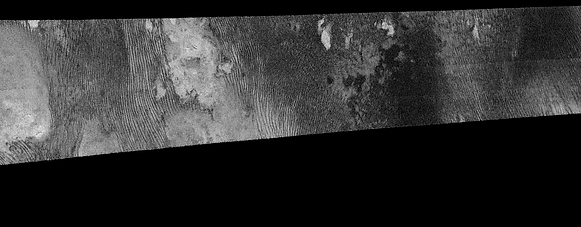

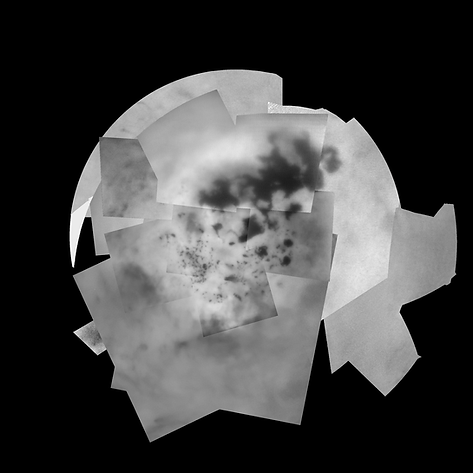

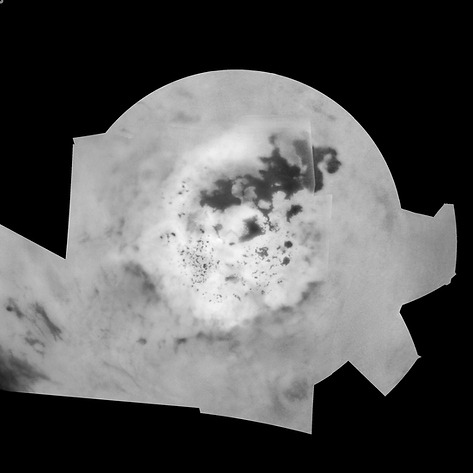

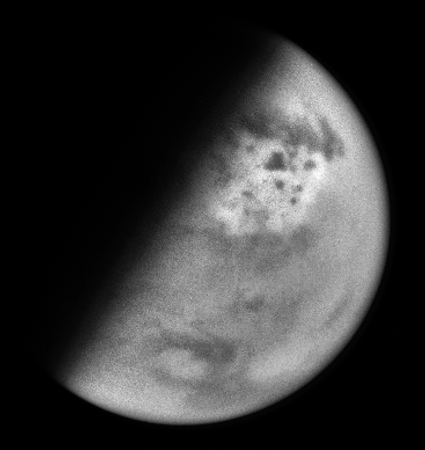

Figure 3 - Example radar snippet: original (BIB)

Figure 3 - Example radar snippet: beam map (BIM)

Figure 3 - Example radar snippet: final version.

Figure 4: Original USGS ISS mosaic, showing flaws and gaps at poles (with magnified inset).

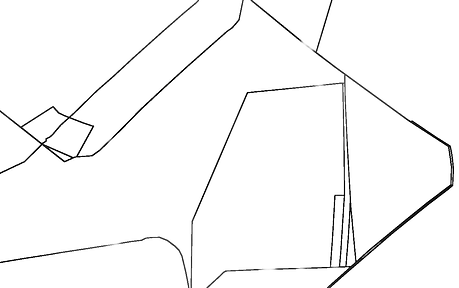

Figure 5: The labelled ‘block map’, showing all 105 blocks.

Figure 6: Example of original block

Figure 6: Example of inpainted seams

Figure 6: Example of fragment map

Figure 6: Example of final restored block.

Figure 7: GIF animation of original vs restored USGS.

Figure 8: Repairs to USGS (Fensal Aztlan & Ching-Tu) using PDS data.

Figure 8: Repairs to USGS (Fensal Aztlan & Ching-Tu) using PDS data.

Figure 8: Repairs to USGS (Fensal Aztlan & Ching-Tu) using PDS data.

Figure 8: Repairs to USGS (Fensal Aztlan & Ching-Tu) using PDS data.

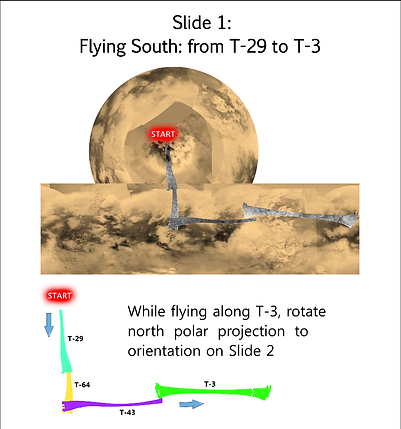

Figure 9: Storyboard examples.

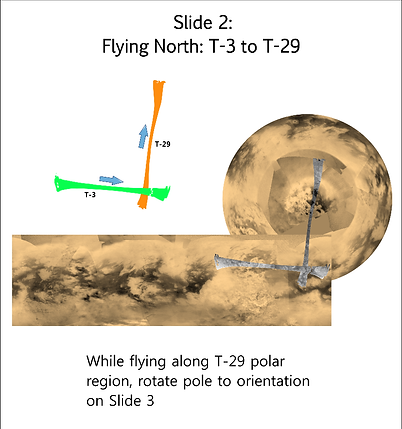

Figure 9: Storyboard examples.

Figure 11: CB3 frame (surface)

Figure 11: CB3 frame ratio result

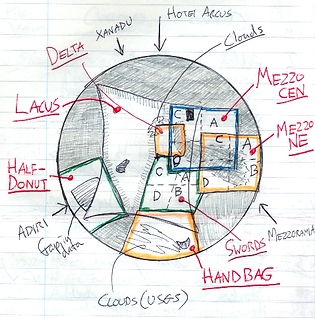

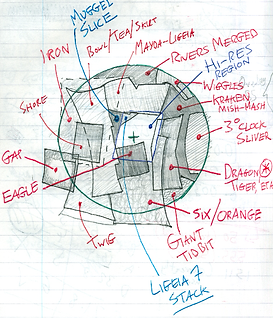

Figure 12: Excerpts from Titan journal, including maps of both poles.

Figure 12: Excerpts from Titan journal, including maps of both poles.

Figure 12: Excerpts from Titan journal, including maps of both poles.

Figure 13: High-resolution mosaic of lake district

Figure 14: Distant frame of Titan from September 2013

Figure 15: merging of footprints: (a) original, (b) high-pass, (c) low-pass, (d) final

Figure 16: Early iteration / (north pole).

Figure 16: Final iteration (north pole).

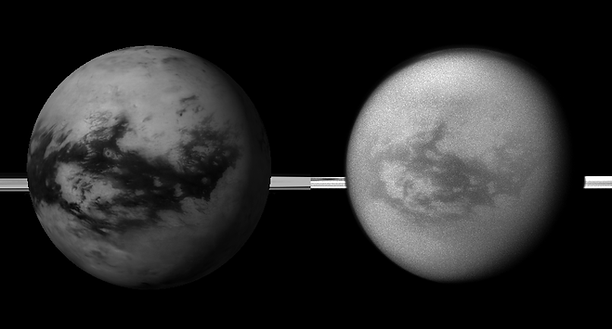

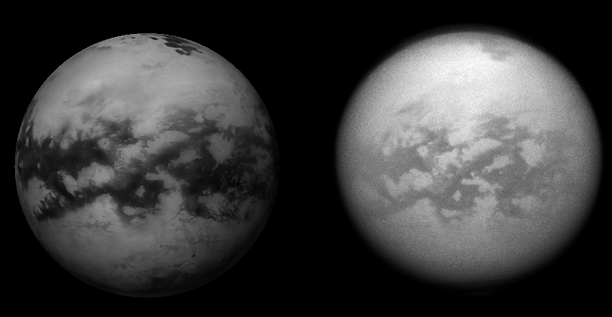

Figure 17: global views of Titan used as albedo references.

Figure 17: global views of Titan used as albedo references.

2. EQUATORIAL FULL: same as above, including the newly processed polar regions.

3. POLAR (N & S): Standard polar projections extending from pole to equator.

4. POLAR EXTENDED (N & S): Same pixel scale as above, but extending 45 degrees in latitude past the equator.

515 radar swathes processed and de-seamed by contributor Jacek Bobowik.

Figure 19: Screenshots of Celestia simulated flyover of ground track.

Figure 19: Screenshots of Celestia simulated flyover of ground track.

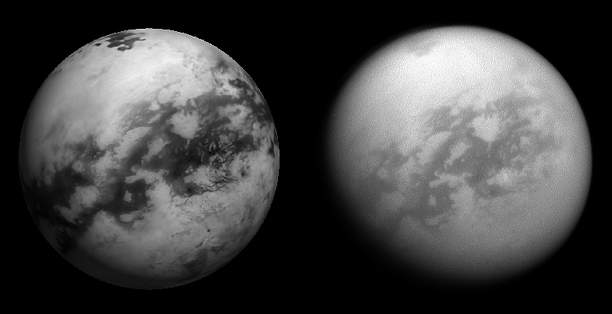

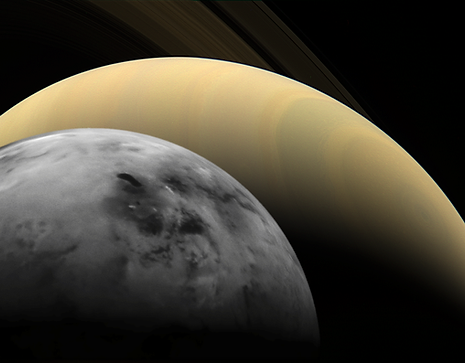

Figure 20: Celestia simulated views vs. Cassini global shots.

Figure 20: Celestia simulated views vs. Cassini global shots.

Figure 20: Celestia simulated views vs. Cassini global shots.

Figure 21: Early version of Dan’s Huygens mosaic

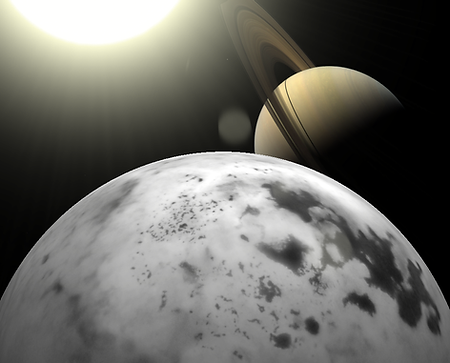

Figure 22: Oblique, artistic view of polar regions

Figure 22: Oblique, artistic view of polar regions

2018 Improved Titan Mosaic